I can’t promise that this will be a weekly series yet, but I want to get it rolling anyway. I’ve wanted to talk about worldbuilding on a regular basis here for months, I just haven’t been able to find the time to do it. A believable setting is essential to fiction. I think of it as one of the big three (believable characters and a compelling plot are the other two). A good setting alone doesn’t get you a good story, but a bad setting will certainly prevent a story from being good. “Worldbuilding” is a term used by some genres (especially sci-fi and fantasy) for the techniques that go into creating a believable setting.

Since my own worldbuilding activities are focused solely on a single fantasy world, that’s where my examples will come from, but many worldbuilding techniques can be applied to other genres. There are lots of ways to begin the construction of the world. Tolkien famously started with a set of fictional languages. You can start with a town, say, or a character, and work outward from there. You can also start at the macro level – an idea for a planet, for example, then zoom in and add the details.

My own world started with a basic outline of a continent that I sketched on a piece of graph paper when I was 16. It’s evolved since then. The continent’s been inverted and moved to the southern hemisphere. I decided to place the continent on an earthlike planet. All but a handful of the original country names have changed. I know there are two other continents on the planet, but I haven’t spent any time detailing them, and I never will unless I need them for storytelling purposes.

I already have the basic info for more than 20 countries and a detailed-enough map to keep time and movement straight for a continent almost as big as the Americas. Detailing another continent would be a waste of my resources at this point. It’s enough to know the relative sizes, locations, and general info about the inhabitants of the other two.

At some point, as I was building this world, I decided the geography needed to make rational sense. I’m okay with all manner of fantastical goings-on in fiction. I even enjoy things like a world riding through the cosmos on the backs of four elephants carried by a turtle. But if the story is set on a planet, I don’t want to see a desert right up against the windward side of a mountain range without a good explanation. I also think it’s important, with fantastical stories, to have enough realistic elements to keep readers from being completely disoriented. My realistic elements of choice are the geographical and the social. Here are a few tips to help you out with geographical realism. They’re simple, but you’d be surprised at how many people don’t think about them, and how easy they are to forget during the excitement of creation.

1. Rivers always flow in one direction: downhill. They don’t follow compass points and they don’t necessarily end at the sea (although most do).

2. Rivers nearly always fork upstream, because rivers tend to flow together (they’re all running to the lowest point they can reach).

3. Mountains tend to come in long, relatively thin formations. As a general rule, the taller the mountains, the younger they are. This is because new mountains are formed by seismic activity at the boundaries of tectonic plates, then eroded for hundreds of thousands of years.

4. Heavy mineral resources like iron and gold are more difficult to get at in younger mountains than in older ones. Unless your fictional society is very advanced with their mining, this means these resources will be more scarce in younger mountains.

5. Populations cluster around food and fresh water first, then near valuable resources and along trade routes. This is doubly true in worlds with no railroads or air travel. Most of the largest cities in the world are situated on rivers, on coasts, or both. This is important. Mass migrations are usually caused by either extreme scarcity or armed conflict.

6. When populations are small, terrain is rough, and long distance travel is difficult to manage, big population centers will tend to be city-states. To have large territorial countries of any kind, you must have a central authority with both the population and the technology enforce its writ over a wide area.

7. That’s not to say the technology has to be advanced, nor that the population has to be big in modern terms. A leader with a few thousand square miles of river valley to produce food, neighbors who also live on plains, and knowledge of chariot-making can get into the empire business easily enough. A leader who relies on foot soldiers and lives in a mountainous region with low food production will have a much more difficult time of it, though.

Of course with gods, wizards, or properly-equipped engineers, it’s easy enough to get around this stuff in fiction. I’m not saying every created world has to be geographically consistent. But I find that it helps me get into the story when the geography works — especially if the story is obviously set on a planet.

Here’s a quick-and-easy way to start a setting from scratch. First, draw a line on a piece of paper and make sure it isn’t too straight.

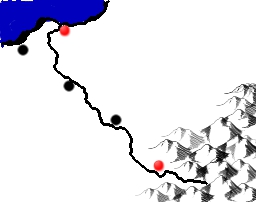

You’ve just drawn your first river. Mine’s a little crude, but that’s ok. We’re not producing finished graphic art here. Were doing a minimal amount of work on the setting so we we can get back to characters and plot. Now, decide which way you want your river to flow. Put a mountain range at the source and a bit of coastline at the mouth.

Now you have some elevation and places for people to live. Put in a few dots to represent a town or three.

Now all you need is to think up a few place names and figure out whether you’re looking at a single country or more than one ( I went with two – the red dots are capitols), and you’ve got the beginning of a fictional setting. If all you need is a single town to set a short story in, you don’t need much more than this. You just need to figure out what sort of town it is and which dot represents it. If you need to do more fleshing out, just keep in mind, as you add additional elements, that the mountains and the mouth of the river are showing you topographical extremes.

Have a great weekend, and thanks for reading! Feel free to share your own worldbuilding tips on the thread.

Here’s a blog about Worldbuilding you might like: Cartography of Dreams. Their latest post is about a Tolkien poem, which is a cool coincidence, since I’m going to work on the next installment of my Tolkien series for Part Time Monster next. My friend Hanna of Things Matter turned me on to CoD.

This gets a bit more complicated when you’re dealing with system-spanning empires, and you start imagining models built with Styrofoam that you’ve carved to fit together properly. Sooner or later I need to formalize where everything is in The Benevolence Archives. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

LOL, indeed. I’d be unhinged if I tried to write interstellar sci-fi for that very reason. Fortunately for me, a single continent is enough to make me happy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is one of the bigger Star Wars influences that I haven’t talked about on BA, actually: Go ahead, tell me how long it takes to get from Hoth to Dagobah. In fact, tell me how much time ANY SW movie takes up. Can’t do it, right? I’ve wholly stolen that sort of unconcern with interstellar geography; I refuse to worry about it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Heh, I was thinking the same thing. I feel like writing space opera is very freeing, I can just not even CARE about some stuff. 😉 My book follows a bunch of characters wandering around from planet to planet, so I can just fill in details as I need them and not worry about the rest of each planet. I’m intending to go back and layer in some fun sci-fi details, but it’s largely window dressing and minor plot complications.

LikeLike

Wow. I don’t think I’d previously been grateful for being less imaginative! My settings are based on real places, which must surely save me some grief. Very good points about the geography. Very good points.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Cartography of Dreams and commented:

I had planned on eventually writing a post about making believable geographies, but this article explains it better than I could have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL Well you beat me to the worldbuilding punch … I’ll just have to tweak my in-progress post a little … 😀

LikeLike